Chapters 1 – 6

Chapter 1

JAC HOLZMAN: My first real job was sorting invoices in the office of a doll manufacturer. Then I worked as a statistician for Picker X-Ray, keeping track of film shipments. Another summer I went to Cincinnati to work for my uncle Saul in his waste materials business. One lesson from that adventure was that I did not ever want to work to someone else's timetable, and never for anyone but myself.

Chapter 2

JAC HOLZMAN: For the first five years I never had a financial balance sheet because I had never heard of one; and since there were no profits there were no taxes.

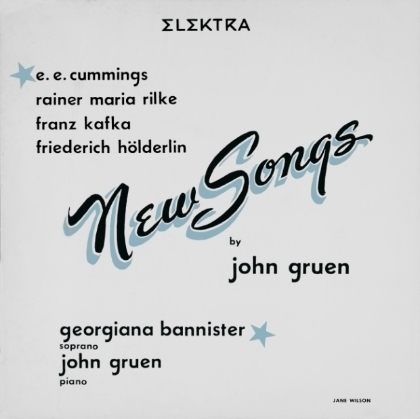

The transition from red ink to black had resulted from a happy convergence of events. Clearly the most important were our artist signings, but I was also searching for a way to take our specialized and distinctive catalog and have it heard by more people. My concept—I have always been big on concepts—was a sampler LP: a collection of musical trailers, a compendium of carefully assembled material, with lyrics and notes, all on a 10-inch LP that would sell for a bargain price unheard of in 1954: $2.00.

Chapter 3

BILL HARVEY: The first time I came across Jac, it was back when he was still working in his record store. He was a strange dude, about six foot four, and I'm six foot two, and we were both skinny, and I didn't like tall skinny guys. He looked too much like me and I looked too much like him, and I thought, "I'm not going to get along with him."

He takes me to his apartment and he puts on a tape and plays the most god-awful music I ever heard: "O' Lovely Appearance Of Death." I had never been subjected to this kind of music before. Everything a cappella, no guitar, just this girl, and she sang and sang, and I sat there for forty minutes, and it was July, he had a skylight in this room and the sun was pouring down, it was like five-thirty in the afternoon—you know the Village, sweat was pouring off me. Jac says, "It's exciting, isn't it? Can you do something with this?" I needed the money, I have kids, and it's fifty bucks. I said, "Well, let me work on it, you know."

Chapter 4

JAC HOLZMAN: There was a psychological as well as a continental divide between East and West. The West Coast was a world afar where life was defined differently. In New York nobody took California seriously, except perhaps San Francisco. Other than the four majors, no East Coast record companies staffed offices there. Records that were successful in the East tended to travel West but not the reverse. I had a hunch something was going to happen in California, and when it did I wanted to be there first.

Chapter 5

PAUL ROTHCHILD: There are all these people who have the talent, and then there are these breakthrough writer-artists who change the way popular music can be made.

Dylan did it first through Peter, Paul and Mary, when they hit with 'Blowing In The Wind,' and of course his own success came after that. And the Beatles did it with their first album. I don't know anyone who didn't love that first album. Everybody from the hardest core Appalachian singer to Roger McGuinn, they all loved it. The first week the Beatles were on the radio, the possibilities changed—the world changed.

![Chapter 6 PAUL NELSON : Phil [Ochs] told me this story. He had spent weeks writing 'Changes,' which was sort of away from his usual topical themes, and he was pretty proud of this song. [Bob] Dylan dropped over to his apartment and Phil wanted](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52e81468e4b047367ade63c1/1395694322413-C7TXF8MRUN1YUDB0G45D/Phil_Ochs_Album_Cover.jpg)

Chapter 6

PAUL NELSON: Phil [Ochs] told me this story. He had spent weeks writing 'Changes,' which was sort of away from his usual topical themes, and he was pretty proud of this song. [Bob] Dylan dropped over to his apartment and Phil wanted to play it for him, and Dylan said, "Oh yeah, here's something I just knocked out in ten minutes, tell me what you think." And it was 'Like A Rolling Stone.' Phil worked on his song for two months, and this guy bashes out 'Like A Rolling Stone' in ten minutes on the way over to your house. That was the position they were all in.

Chapters 7 – 12

Chapter 7

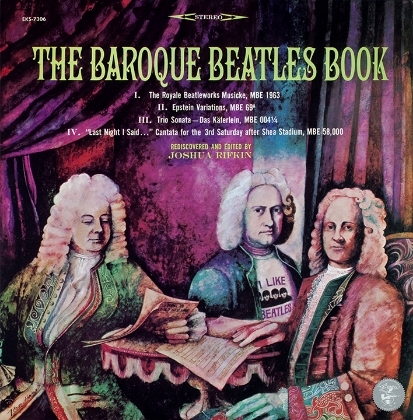

JAC: I called Mark Abramson and Steve Harris together and asked them about doing Beatles songs that would lend themselves to baroque interpretation, as a serious musical exploration, but packaged with humor and an eye toward the Christmas season. The gating issues were who would do the arrangements, and could I get permission from the Beatles.

Dick James was a music publishing legend and guarded the copyrights like the golden goose it was. [I flew to London and] Dick was heading over to the studio to see the boys [Beatles] and I tagged along. Dick went in first while I waited. In a few moments he came and got me, and I made my very simple pitch. John Lennon's first comment was, "You did Koerner, Ray & Glover." I nodded a proud "Yes." "Well, that's alright then. Anyone who records Koerner, Ray & Glover is OK with me."

![Chapter 8 JAC : That evening [at the Newport Folk Festival] I was standing next to Dave Gahr in the photographer's pit, below and in front of the stage. Peter Yarrow introduced [Bob] Dylan for the very special artist that he was, and from t](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52e81468e4b047367ade63c1/1395675669338-Z2E52NS8TE122HKJG4TT/CH_8_Butterfield_East_West.jpg)

Chapter 8

JAC: That evening [at the Newport Folk Festival] I was standing next to Dave Gahr in the photographer's pit, below and in front of the stage. Peter Yarrow introduced [Bob] Dylan for the very special artist that he was, and from the moment he launched into 'Maggie's Farm,' now fleshed out with an incredible electric intensity, it was clarity and catharsis. My friend Paul Nelson of the Little Sandy Review was standing alongside, and we just turned to each other and shit-grinned. Then suddenly we heard booing, like pockets of wartime flak. The audience had split into two separate and opposing camps. It grew into an awesome barrage of catcalls and hisses. It was very strange, because I couldn't believe that those people weren't hearing the wonderful stuff I was hearing.

PAUL ROTHCHILD: I was at the console, mixing the set, the only one there who had ever recorded electric music. I could barely hear Dylan because of the furor. From my perspective, it seemed like everybody on my left wanted Dylan to get off the stage, everybody on my right wanted him to turn it up. And I did—I turned it up.

Chapter 9

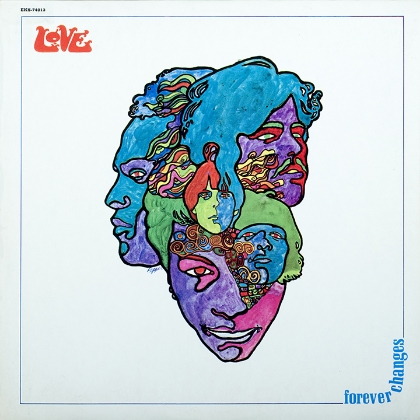

MARK ABRAMSON: Love, the whole band, was just about as strange as you could get. And Arthur—what an incredible guy. He was this kind of brooding, dark presence. He wore these jeweled glasses that he obviously couldn't see through, low on his nose. He always looked at you over them, so he had this look of a kind of berserk intellectual or teacher or a judge or a guru of some sort.

ADAM HOLZMAN: Arthur took me up to his place. I was nine. He drove really fast and I was scared to death and I thought it was the most exciting thing in my life. We sat around and listened to the new Jimi Hendrix "Are You Experienced" album. Arthur loved Jimi Hendrix, and he played that record over and over again. He kept getting up and saying, "I'm going to have to listen to that one more time." And he would put it back to 'Purple Haze.'

Chapter 10

PAUL ROTHCHILD: Jac was on the perimeter of the American music scene which would become mainstream within three to five years. We had stuff on record and out years before the rest of the world got onto it. So the Elektra image of being very avant garde, very hip, was maintained.

LENNY KAYE: At college I started noticing that a lot of records that I was gravitating towards were Elektra releases, especially after the first Love album. Any record I bought on Elektra would prove interesting. I found their signings to be fascinating. Definitely intellectually challenging. No other label was like that. They were cutting edge.

![Chapter 11 BILL SIDDONS: Paul [Rothchild] was the smartest guy about the business that I knew. And a kind of intense, consumed-with-passion-for-life kind of guy. Always an enthusiast, a real positive force. He was also the only guy w](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52e81468e4b047367ade63c1/1395676202306-KUUUWRIBR130FABKZU0F/CH_11_Doors_First_Album_Cover.jpg)

Chapter 11

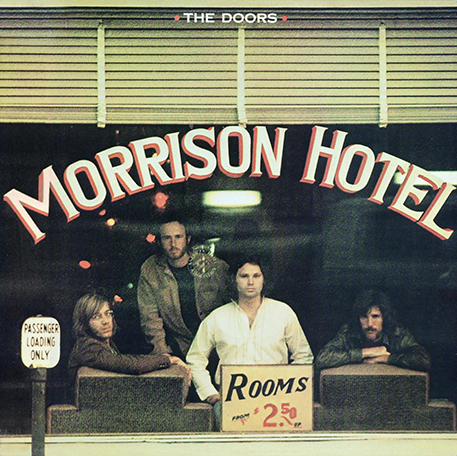

BILL SIDDONS: Paul [Rothchild] was the smartest guy about the business that I knew. And a kind of intense, consumed-with-passion-for-life kind of guy. Always an enthusiast, a real positive force. He was also the only guy who could intimidate all The Doors.

PAUL ROTHCHILD: I didn't want a Doors record to sound like anybody else's records, because that's like buying bread, it becomes stale very quickly. But if you create your own sound, if you've got something unique, the best thing you can do is keep it as pure as possible, so that it's not copyable. For example, Robby Krieger was enchanted with the wah-wah pedal, which Jimi Hendrix is associated with. But you could buy that off the shelf, and it immediately made any guitar player sound like any other guitar player. Instead I said, "I prohibit you from using off-the shelf material. Create it. Invent it."

![Chapter 12 SUZANNE HELMS: Jac couldn't have found anybody more perfect for that period of his life. [His wife] Nina related well with the artists, she loved the music, she helped with the company. PAUL ROTHCHILD: From the first day](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52e81468e4b047367ade63c1/1395676391318-7ZL1URBF8N3CCUL4T4MH/CH_13_Color_Butterfly_Logo.jpg)

Chapter 12

SUZANNE HELMS: Jac couldn't have found anybody more perfect for that period of his life. [His wife] Nina related well with the artists, she loved the music, she helped with the company.

PAUL ROTHCHILD: From the first day I joined the company, Nina was an active part of the A&R department. Never in title, but she was always actively involved. Elektra was not just the business her husband was in, she was an integral part of it. She'd go out to the clubs during times when Jac couldn't. And once the artist was signed, she was very much involved in liaison, maintaining loving and positive contact. She was very bright, very giving. She was—what's the phrase I'm looking for?—the patron saint of A&R.

Chapters 13 – 18

Chapter 13

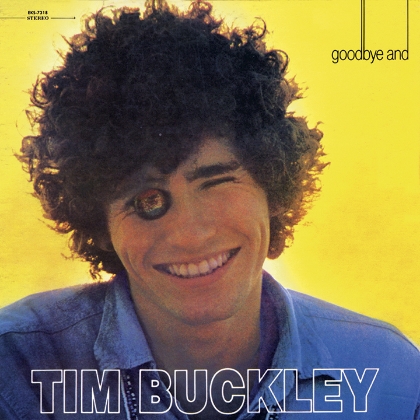

DAVID ANDERLE: Tim Buckley was already signed when I came to Elektra.

JAC: Herbie Cohen had sent me Tim's demo.

HERB COHEN: One of the great voices of our time. He had a four-octave range, five if he wanted to stretch it. Just brilliant.

ELLEN VOGT: I adored Tim. I had a big crush on him. I used to look out the window to see if he was coming.

PAT FARALLA: A slightly slouching and shy young man, beautiful, hair like a halo, befitting yet another angel. I was in love with this young voice, those words, that torment, that frustration, that poet.

![Chapter 14 BILL HARVEY: For the cover [of Strange Days], I didn't want to have to deal with the group, it was too difficult. I talked to them, and they agreed instead on something Fellini-esque, a troupe of strolling players idea. I shot at Sn](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52e81468e4b047367ade63c1/1395679172611-8T1WOWOL28HVVYVA9MBS/CH_14_Doors_Strange_Days_Album.jpg)

Chapter 14

BILL HARVEY: For the cover [of Strange Days], I didn't want to have to deal with the group, it was too difficult. I talked to them, and they agreed instead on something Fellini-esque, a troupe of strolling players idea. I shot at Sniffen Court, a mews between Lexington and 3rd Avenue, in New York. I gathered people from all over. I went up to this strange residential hotel, on Broadway in the Seventies. Very, very old place. Odd people were there. I was looking for these twin midgets. I knocked on the door and the door opens and I look down and there they are. I came in, and they had all their clothes laid out on the bed. They were as neat as pins, I mean everything was just perfect. They were just sweet people, awfully nice men. "Do you want us to wear this? Or do you want us to wear that?" I got a strong man from the circus. I found an acrobat guy. I got the photographer's assistant to put makeup on and I let him juggle some balls. I took a taxi driver and pulled him out of the cab and said, "For five bucks, will you stand over there and blow a trumpet?" Because he had on this battered old hat and I thought, he's perfect.

Chapter 15

JAC: In October of 1966, when I had a fully mixed first Doors album, I played it for Judy Collins. None of our artists had yet heard it but they were all very curious, and I wondered if Judy would get it. She surprised me with her all-out enthusiasm. Judy understood that The Doors were a new voice for the label.

What I was doing with The Doors was following the music, as I had done all along—from folk to singer-songwriters, to Koerner, Ray & Glover, to the Butterfield Blues Band, to Love, to The Doors

![Chapter 16 JUDY JAMES: I had an impression of Barry [Friedman] as a true hippie. In the way that Cass Elliott was a true hippie. They believed in what was going on. They believed in what Timothy Leary was finding out, and didn't yet know](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52e81468e4b047367ade63c1/1395679332887-93DDSCB4KMKN1INO4785/CH_16_Holy_Modal_Rounders_album_cover.jpg)

Chapter 16

JUDY JAMES: I had an impression of Barry [Friedman] as a true hippie. In the way that Cass Elliott was a true hippie. They believed in what was going on. They believed in what Timothy Leary was finding out, and didn't yet know the danger of it, that it was only true for five minutes and then you could be lost to the acid experience.

JOHN HAENY: There were [lots of] social experiments at [Barry's] house.

BARRY FRIEDMAN: One time Nico came in with a gun and grabbed some woman that one of the boys was in bed with by the hair and drug her out and made her run down the road, and we finally got the gun away from Nico and said, "Nico, why did you do that?" And she said, "Oh, some men like that."

JACKSON BROWNE: You'd meet all sorts of great people at Barry's house. That's where I met Warren Zevon. I met David Crosby there. He and Stephen Stills and Graham Nash would come over and play their demo.

![Chapter 17 JANICE KENNER : Let me just think if I can really recount what happened that evening. OK, here we go. We decided to ply Jac with [marijuana]-filled Cornish hens. There were dancing girls, then there was a bath, and there were women wi](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52e81468e4b047367ade63c1/1395679447062-9M2KTGWH8IXZFDFLR083/CH_17_Running_Jumping_Standing_Still.jpg)

Chapter 17

JANICE KENNER: Let me just think if I can really recount what happened that evening. OK, here we go. We decided to ply Jac with [marijuana]-filled Cornish hens. There were dancing girls, then there was a bath, and there were women with no clothes on, and Jac was like, "No, I can't, I can't, wait, please, no," and they cajoled him, I swear to God he fought, he was so resistant, but somehow they managed to get him in this tub.

Chapter 18

JAC: To deal with the whole culture of music in the late Sixties, the established record companies, which had always been run by suits, would, out of bafflement with the new scene, hire designated counter-culture types to be ombudsmen between the company and the artist. They were called "company freaks." They were fertile sources of gossip and some gossip was of inestimable value. Our New York company freak was Danny Fields.

STEVE HARRIS: I loved Danny. He would stay out late, and if he had copy due by three o'clock, he would stagger in at two, write this magical stuff and then leave. Nobody else had a Danny Fields working for them.

JANN WENNER: Danny was the hippest guy in New York

Chapters 19 – 24

Chapter 19

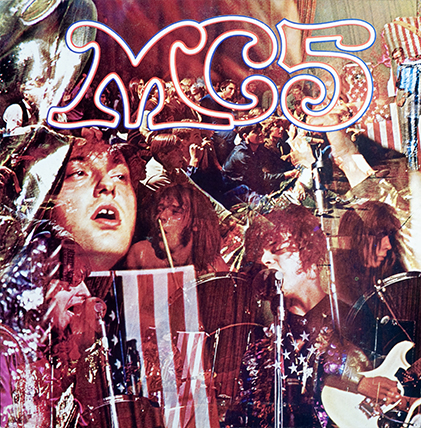

JAC: Danny was responsible for bringing us MC5, a revolutionary (in the sense of "overthrow") counter-culture band. I found myself dealing with John Sinclair, chief factotum of the White Panthers.

DANNY FIELDS: John Sinclair was a friend of friends of mine, and my friends persuaded me to go out to Detroit and have a look at MC5. I had started to assume A&R duties. So out I went. I stayed in Sinclair's house, in the commune.

JAC: Danny had immaculate taste for the arcane and he knew I'd go for it, so his commitment to Sinclair was in the bag before I knew what he had been up to. But I was intrigued by how the MC5 maneuvered their music to drive their politics, like a loudspeaker assault on the established order: Who is on the inside, who is on the ramparts?—a rock and roll equivalent of storming the battlements.

![Chapter 20 STEVE HARRIS : One time [Iggy Stooge] was working at Max's Kansas City, and at the end of the gig, it must have been about three in the morning, he says, "Where are you going?" I said, "Home." I lived on East 82nd. He says, "Well, I'](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52e81468e4b047367ade63c1/1395681775402-HYFK7W7I2QQAOUNPF14T/Stooges_Album_Cover.jpg)

Chapter 20

STEVE HARRIS: One time [Iggy Stooge] was working at Max's Kansas City, and at the end of the gig, it must have been about three in the morning, he says, "Where are you going?" I said, "Home." I lived on East 82nd. He says, "Well, I'm going to see this girl I know on Park Avenue in the 70s." I said, "Well, I'll drop you off."

Iggy was appearing on stage in a diaper, and he had cut himself up unmercifully, he was bleeding like crazy, and you'd think that he would change to go to Park Avenue and 72nd. But no. My attitude was, this is rock and roll—if Iggy Stooge wants to see some chick on Park Avenue in a diaper, bleeding from the waist up, that's his prerogative, he's the artist. He got out of the cab and said, "Come on up with me, have a drink." So there's this really lovely Park Avenue apartment building. The doorman's in full regalia. Iggy asks for this girl. The doorman is looking at him like he is absolutely out of his mind. "Who shall I say is calling?" Iggy says, "Tell her Iggy's here." And she says, "Send him up." All the way up, the elevator operator's looking at Iggy in his diaper, bleeding. We get there and it's this magnificent apartment, just like you see in the movies, and a girl answers in a negligee, slinky, a tall Lauren Bacall-looking woman. We had a couple of drinks, then I left, and Iggy stayed. The next day he called me at the office: "I can't work tonight, I had thirty-two stitches this morning."

Chapter 21

MARK ABRAMSON: I was very interested in alternative lifestyles, the idea of the Woodstock nation, talking it up a lot. There were enough of us who were thinking of that, and we met. I did an introduction: "Why don’t we live communally? We went around the room, and everybody had an entirely different idea of what they wanted to do. Including, "I don’t want to belong to any kind of group," or "I don’t want to do anything," from "We should be politically active, support Chavez’s grape strike," to "Let’s go away and buy four hundred acres and make our whole commitment." Totally chaotic, and I’m pissed, because I had a very specific idea in mind. So we decide to have another meeting, just for the people who are interested in alternative lifestyles, so we can be focused. It’s in Judy Collins’s living room on West End Avenue, packed, there’s got to be thirty people in the room, most of them people I’ve never seen before.

Chapter 22

KEITH HOLZMAN: I negotiated our lease for our offices at the new Gulf & Western building.

We watched the building go up literally from the point they excavated. We spent a quarter of a million to design and furnish over ten thousand square feet of open space.

The elevator doors had Elektra logos covering the entire door. Every time the elevator stopped on our floor, the occupants knew we were there. In the reception area we had slide projectors with a little controller, projecting scenes of Elektra artists and events. For our lighting we made reflectors from record stampers that we got from our pressing plant, sixty to eighty of them, running along the entire hallway in the front part of the building.

![Chapter 23 JAC : The day before signing [the sale of Elektra to Warner], I called all the staff into the Elektra conference room to tell them what was happening. I spoke for about five minutes, then took questions for another forty-five. ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52e81468e4b047367ade63c1/1395784817986-9SKUG5A6LNSNQGI3E9NB/Waitin_For_the_Sun.jpg)

Chapter 23

JAC: The day before signing [the sale of Elektra to Warner], I called all the staff into the Elektra conference room to tell them what was happening. I spoke for about five minutes, then took questions for another forty-five. I called the key artists personally and most caught my enthusiasm, or at least said they did.

Finally, I divided $1,000,000, pre-tax, among those who had phantom stock options and were required to tender their "shares," and Bill Harvey, Mel Posner, Russ Miller and the others who have served. I made out thirty-two checks in all. When the word got out about this million-dollar distribution—the fact of it and the size of it—I was regarded by some in the business as a saint, and by most entertainment-business lawyers as just plain crazy.

Chapter 24

JAC: I told Bill Harvey I wanted a place north of the city, about an hour's commute, and would he keep his eyes open? A few days later Bill said, "I think I've found something that would be perfect for you, in South Salem, just a few miles east of the thruway." I made arrangements to see it the very next weekend.

The land was forty-six glorious rolling acres with a driveway that ran a quarter mile from the main road to the house. The house itself was a barn, built in the latter part of the eighteenth century, dismantled and reassembled, turned inside out so that the weathered wood gave the interior a stunning patina of antiquity. It was wonderful and livable. I bought it for $250,000, money from the sale. Ellen christened it 'Tranquility Base,' after the Apollo astronauts' first landing zone on the moon.

ELLEN SANDER: In the center of the living area we put a water bed and a hammock. My [office] room looked out over the pool. It was set into this beautifully manicured lawn. We kept it heated in the winter, there would be snow on the ground, the pool would be steaming, and ducks would be floating on the water.

Chapters 25-32

![Chapter 25 JUDY COLLINS : I said to Mark [Abramson] and John [Haeny], "Where to record ["Amazing Grace"]? What's wonderful?" Mark had gone to Columbia and knew about St. Paul's chapel. He and John went up and took a look, and it was ideal, a b](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52e81468e4b047367ade63c1/1395784978796-Q9KD7TAX3L0XARYI3JE8/Whales_and_Nightengales.jpg)

Chapter 25

JUDY COLLINS: I said to Mark [Abramson] and John [Haeny], "Where to record ["Amazing Grace"]? What's wonderful?" Mark had gone to Columbia and knew about St. Paul's chapel. He and John went up and took a look, and it was ideal, a beautiful, tiny little round-domed stone-tiled cathedral, green tile, with a stained glass window.

MARK ABRAMSON: There was just something about it, a spirit.

JUDY COLLINS: John set us up. For on-site recording, there was nobody better.

JAC: Everyone was grouped at the choir end, like a platoon of voices in a shower, but smoothed out and sounding great. The mood was joyous and affirming.

MARK ABRAMSON: It was almost heavenly, but not choir-like. It doesn't sound like a select choir. It's real down to earth. It was exciting, playing it back in the church, with all of those people, and everybody was just—"Jesus!" Then sitting in the van we had outside, listening to it, I knew we had something hair-raising.

JOHN HAENY: Putting that album together was a magical experience, one of the two best in my career. It was a brilliant record, on all levels, an enormously broad tapestry of music, big classical works, little folk works, esoteric works.

Chapter 26

JAC: The summer that Judy Collins recorded 'Amazing Grace,' Jim Morrison finally went on trial in Miami—August, 1970.

The proceedings were politically charged and painful, the verdict convoluted. The judge sentenced him to sixty days of hard labor for profanity, and for indecent exposure six months of hard labor plus a $500 fine. He was expected to serve two months, with the other four months on probation, plus an additional two years probation. Jim remained free on bail pending appeal. In other words, it wasn't over and it wasn't going to be over any time soon.

ROBBY KRIEGER: At the time we didn't realize what a great guy Jac was. A guy who is able to succeed without screwing people. He's really the only guy I know who is a totally great businessman and totally generous.

![Chapter 27 JAC : During the last week of August, 1970, Ahmet [Ertegun] and I were in London to discuss recording the Isle of Wight festival, the big European outdoor festival of the summer. Ahmet is staying at the Dorchester, but hi](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52e81468e4b047367ade63c1/1395683310073-YGJPEQYYA4SY46W6MVQ1/Lindisfarne_Album_Cover.jpg)

Chapter 27

JAC: During the last week of August, 1970, Ahmet [Ertegun] and I were in London to discuss recording the Isle of Wight festival, the big European outdoor festival of the summer. Ahmet is staying at the Dorchester, but his mind is not on the Isle of Wight. Ahmet has been chasing Mick Jagger for over a year, trying to bring the Stones to Atlantic. He gets on the phone to Mick and recaps what a great evening they just shared, fabulous music, wonderful ladies, and isn't it time they cut a deal. Mick says he will be happy to talk to Ahmet about the Stones recording for Atlantic—just as soon as he has spoken to Clive Davis at Columbia. And Mick hangs up. Ahmet goes ballistic. Before my eyes he is slowly, and uncharacteristically, coming unhinged, really pissed but struggling to regain control. Then a beatific calm smoothes the angry lines in his face and he picks up the phone, very deliberately dials, and says, "Mick, I can understand that you want to talk to Clive Davis, and you should. But I want you to know that I can only make one Stones-size deal this year, and it's either you"—long exquisitely-timed pause—"or Paul Revere and the Raiders." And he hangs up. Twenty seconds later the phone rings. We both know it's Mick, but Ahmet doesn't pick up. We go back to talking about the Isle of Wight.

![Chapter 28 STEVE HARRIS : [Before her premiere performance at the Troubadour] Carly said, "Can I go down and talk to everybody? Make friends with them?" I said, "No, you can't." She said, "Can we go for a walk?" I said, "Yes, we can." We walked](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52e81468e4b047367ade63c1/1395694529147-V3LY2EP4FLMJTR4RVYRU/CH_28_Carly_Simon_No_Secrets.jpg)

Chapter 28

STEVE HARRIS: [Before her premiere performance at the Troubadour] Carly said, "Can I go down and talk to everybody? Make friends with them?" I said, "No, you can't." She said, "Can we go for a walk?" I said, "Yes, we can." We walked down the stairs of the Troubadour, Elektra Records is all there, ready to cheer her on, and we walked arm in arm out the door and they think we've split forever, never to return. We come back by the back door, up the stairs, and Carly looks at me and says, "After the show, if Jac Holzman comes backstage and tells me how wonderful I am, 'Carly, you were just fabulous, we're going to be behind you a hundred percent,' I'll know I failed. I'll know he's faking. I don't want to hear that, Steve. Don't let him come back and say that to me."

CARLY SIMON: That sounds just like me.

STEVE HARRIS: So—she goes on. And, she was wonderful, just wonderful. One of those magical nights that you knew she was going to wake up in the morning a star. Everyone comes backstage to pay their greetings and salutations. Of course the first one is Jac. And of course he says, "Carly, you're wonderful. We think you're terrific. Everything you want, we're going to do for you." And Carly's looking at me like—

Chapter 29

PAUL ROTHCHILD: I'd love to know whether Jim actually was searching for his medium, as so many people of great talent have done in the past. I think that perhaps rock was just the convenient medium, the popular one for art. To break through in our time, rock seemed to be the one. I think ultimately if he hadn't succeeded in rock he would have gone in a direction not unlike a Sam Shepard, where he would have been a playwright, an actor, a director. In another time Jim might have been a traveling troubadour, someone who went from town to town with a poem and a little bit of shtick, to entertain people.

Chapter 30

BILL SIDDONS: To me, the consistency in Jim's [Morrison) persona was to push you far enough for you to get out of your shell and to become who you really were at the center. That's what he did to everybody. I had conversations with him where I had to get him to stop because he had taken my mind to places I didn't know how to handle.

He could be the biggest asshole in the world. And he could be one of the finest people you'd ever know. The guy who everybody perceived as nuts, arrogant, in fact was one of the most sensitive and highly developed minds I ever knew. There was a gentle, generous human soul there. And one of my more profound memories is his generosity.

![Chapter 31 JAC : Harry [Chapin] was an extraordinarily fast study. He had the kind of rapid assimilation and facility that Bill Clinton has—in fact he was like Clinton in many ways. He quickly figured how a studio worked, which was important](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52e81468e4b047367ade63c1/1395684309799-GZMTB0PRETQDUZJS2JXJ/CH_31_Harry_Chapin_Heads_Tails.jpg)

Chapter 31

JAC: Harry [Chapin] was an extraordinarily fast study. He had the kind of rapid assimilation and facility that Bill Clinton has—in fact he was like Clinton in many ways. He quickly figured how a studio worked, which was important because the more he knew the more he could conceive of doing. During breaks the band would be taking fifteen minutes and Harry would sit in a corner writing a new song. We talked a great deal about the difference between craft and art. Harry had craft down pat; I was pushing him for more art. After several weeks of pressure-cooker days that went on till we dropped, we became close friends.

Chapter 32

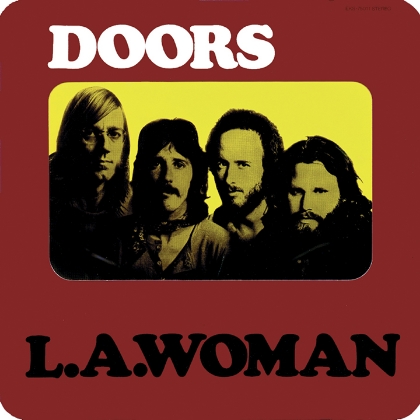

JACK NELSON: Queen reminded me of the makeup of the Beatles. Each guy was so totally the opposite of the others, the four points of the compass. Freddie Mercury was the lead vocalist. He composed on keyboards, and he was classically trained. Very complex guy, incredibly talented. Brian May was a rock and roll guitarist and he brought that influence. Also incredibly talented, scatterbrained as they come, and yet as focused as they come. He had a degree in infrared astronomy. John Deacon was the bass player. He brought the solid bit, as bass players do, grounded them. He had a first-class honors degree in electronics. Roger Meddows-Taylor, the drummer, had a double degree. They were probably the smartest band in the business. And totally diverse personalities—we could get into an airport and one would stop, one would go right, one would go left, and one would go straight ahead. But it made a great creative force. When they got together in the middle, with the stacked vocals, that center was amazing.