Chapters 25-32

![Chapter 25 JUDY COLLINS : I said to Mark [Abramson] and John [Haeny], "Where to record ["Amazing Grace"]? What's wonderful?" Mark had gone to Columbia and knew about St. Paul's chapel. He and John went up and took a look, and it was ideal, a b](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52e81468e4b047367ade63c1/1395784978796-Q9KD7TAX3L0XARYI3JE8/Whales_and_Nightengales.jpg)

Chapter 25

JUDY COLLINS: I said to Mark [Abramson] and John [Haeny], "Where to record ["Amazing Grace"]? What's wonderful?" Mark had gone to Columbia and knew about St. Paul's chapel. He and John went up and took a look, and it was ideal, a beautiful, tiny little round-domed stone-tiled cathedral, green tile, with a stained glass window.

MARK ABRAMSON: There was just something about it, a spirit.

JUDY COLLINS: John set us up. For on-site recording, there was nobody better.

JAC: Everyone was grouped at the choir end, like a platoon of voices in a shower, but smoothed out and sounding great. The mood was joyous and affirming.

MARK ABRAMSON: It was almost heavenly, but not choir-like. It doesn't sound like a select choir. It's real down to earth. It was exciting, playing it back in the church, with all of those people, and everybody was just—"Jesus!" Then sitting in the van we had outside, listening to it, I knew we had something hair-raising.

JOHN HAENY: Putting that album together was a magical experience, one of the two best in my career. It was a brilliant record, on all levels, an enormously broad tapestry of music, big classical works, little folk works, esoteric works.

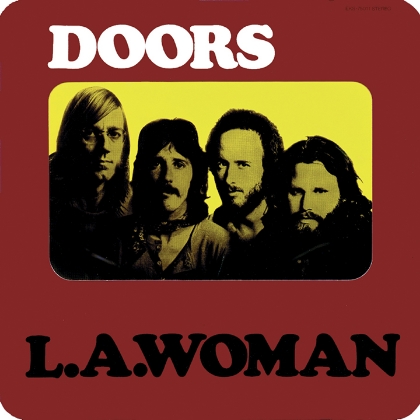

Chapter 26

JAC: The summer that Judy Collins recorded 'Amazing Grace,' Jim Morrison finally went on trial in Miami—August, 1970.

The proceedings were politically charged and painful, the verdict convoluted. The judge sentenced him to sixty days of hard labor for profanity, and for indecent exposure six months of hard labor plus a $500 fine. He was expected to serve two months, with the other four months on probation, plus an additional two years probation. Jim remained free on bail pending appeal. In other words, it wasn't over and it wasn't going to be over any time soon.

ROBBY KRIEGER: At the time we didn't realize what a great guy Jac was. A guy who is able to succeed without screwing people. He's really the only guy I know who is a totally great businessman and totally generous.

![Chapter 27 JAC : During the last week of August, 1970, Ahmet [Ertegun] and I were in London to discuss recording the Isle of Wight festival, the big European outdoor festival of the summer. Ahmet is staying at the Dorchester, but hi](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52e81468e4b047367ade63c1/1395683310073-YGJPEQYYA4SY46W6MVQ1/Lindisfarne_Album_Cover.jpg)

Chapter 27

JAC: During the last week of August, 1970, Ahmet [Ertegun] and I were in London to discuss recording the Isle of Wight festival, the big European outdoor festival of the summer. Ahmet is staying at the Dorchester, but his mind is not on the Isle of Wight. Ahmet has been chasing Mick Jagger for over a year, trying to bring the Stones to Atlantic. He gets on the phone to Mick and recaps what a great evening they just shared, fabulous music, wonderful ladies, and isn't it time they cut a deal. Mick says he will be happy to talk to Ahmet about the Stones recording for Atlantic—just as soon as he has spoken to Clive Davis at Columbia. And Mick hangs up. Ahmet goes ballistic. Before my eyes he is slowly, and uncharacteristically, coming unhinged, really pissed but struggling to regain control. Then a beatific calm smoothes the angry lines in his face and he picks up the phone, very deliberately dials, and says, "Mick, I can understand that you want to talk to Clive Davis, and you should. But I want you to know that I can only make one Stones-size deal this year, and it's either you"—long exquisitely-timed pause—"or Paul Revere and the Raiders." And he hangs up. Twenty seconds later the phone rings. We both know it's Mick, but Ahmet doesn't pick up. We go back to talking about the Isle of Wight.

![Chapter 28 STEVE HARRIS : [Before her premiere performance at the Troubadour] Carly said, "Can I go down and talk to everybody? Make friends with them?" I said, "No, you can't." She said, "Can we go for a walk?" I said, "Yes, we can." We walked](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52e81468e4b047367ade63c1/1395694529147-V3LY2EP4FLMJTR4RVYRU/CH_28_Carly_Simon_No_Secrets.jpg)

Chapter 28

STEVE HARRIS: [Before her premiere performance at the Troubadour] Carly said, "Can I go down and talk to everybody? Make friends with them?" I said, "No, you can't." She said, "Can we go for a walk?" I said, "Yes, we can." We walked down the stairs of the Troubadour, Elektra Records is all there, ready to cheer her on, and we walked arm in arm out the door and they think we've split forever, never to return. We come back by the back door, up the stairs, and Carly looks at me and says, "After the show, if Jac Holzman comes backstage and tells me how wonderful I am, 'Carly, you were just fabulous, we're going to be behind you a hundred percent,' I'll know I failed. I'll know he's faking. I don't want to hear that, Steve. Don't let him come back and say that to me."

CARLY SIMON: That sounds just like me.

STEVE HARRIS: So—she goes on. And, she was wonderful, just wonderful. One of those magical nights that you knew she was going to wake up in the morning a star. Everyone comes backstage to pay their greetings and salutations. Of course the first one is Jac. And of course he says, "Carly, you're wonderful. We think you're terrific. Everything you want, we're going to do for you." And Carly's looking at me like—

Chapter 29

PAUL ROTHCHILD: I'd love to know whether Jim actually was searching for his medium, as so many people of great talent have done in the past. I think that perhaps rock was just the convenient medium, the popular one for art. To break through in our time, rock seemed to be the one. I think ultimately if he hadn't succeeded in rock he would have gone in a direction not unlike a Sam Shepard, where he would have been a playwright, an actor, a director. In another time Jim might have been a traveling troubadour, someone who went from town to town with a poem and a little bit of shtick, to entertain people.

Chapter 30

BILL SIDDONS: To me, the consistency in Jim's [Morrison) persona was to push you far enough for you to get out of your shell and to become who you really were at the center. That's what he did to everybody. I had conversations with him where I had to get him to stop because he had taken my mind to places I didn't know how to handle.

He could be the biggest asshole in the world. And he could be one of the finest people you'd ever know. The guy who everybody perceived as nuts, arrogant, in fact was one of the most sensitive and highly developed minds I ever knew. There was a gentle, generous human soul there. And one of my more profound memories is his generosity.

![Chapter 31 JAC : Harry [Chapin] was an extraordinarily fast study. He had the kind of rapid assimilation and facility that Bill Clinton has—in fact he was like Clinton in many ways. He quickly figured how a studio worked, which was important](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52e81468e4b047367ade63c1/1395684309799-GZMTB0PRETQDUZJS2JXJ/CH_31_Harry_Chapin_Heads_Tails.jpg)

Chapter 31

JAC: Harry [Chapin] was an extraordinarily fast study. He had the kind of rapid assimilation and facility that Bill Clinton has—in fact he was like Clinton in many ways. He quickly figured how a studio worked, which was important because the more he knew the more he could conceive of doing. During breaks the band would be taking fifteen minutes and Harry would sit in a corner writing a new song. We talked a great deal about the difference between craft and art. Harry had craft down pat; I was pushing him for more art. After several weeks of pressure-cooker days that went on till we dropped, we became close friends.

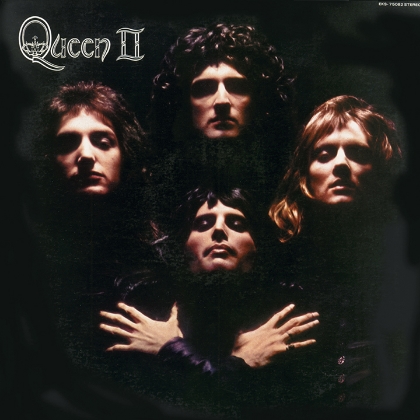

Chapter 32

JACK NELSON: Queen reminded me of the makeup of the Beatles. Each guy was so totally the opposite of the others, the four points of the compass. Freddie Mercury was the lead vocalist. He composed on keyboards, and he was classically trained. Very complex guy, incredibly talented. Brian May was a rock and roll guitarist and he brought that influence. Also incredibly talented, scatterbrained as they come, and yet as focused as they come. He had a degree in infrared astronomy. John Deacon was the bass player. He brought the solid bit, as bass players do, grounded them. He had a first-class honors degree in electronics. Roger Meddows-Taylor, the drummer, had a double degree. They were probably the smartest band in the business. And totally diverse personalities—we could get into an airport and one would stop, one would go right, one would go left, and one would go straight ahead. But it made a great creative force. When they got together in the middle, with the stacked vocals, that center was amazing.